The Process of Breeding a New Turfgrass Variety

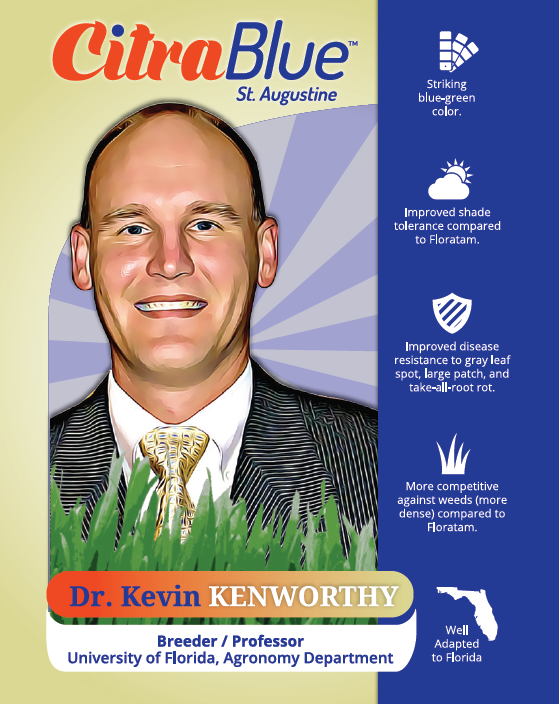

Dr. Kevin Kenworthy, one of the top turfgrass breeders in the country, is a professor in the University of Florida Agronomy Department. His team is developing a number of improved turfgrass varieties. Dr. Kenworthy offers some insight into the turfgrass breeding process and his newest grass, CitraBlueTM St. Augustine.

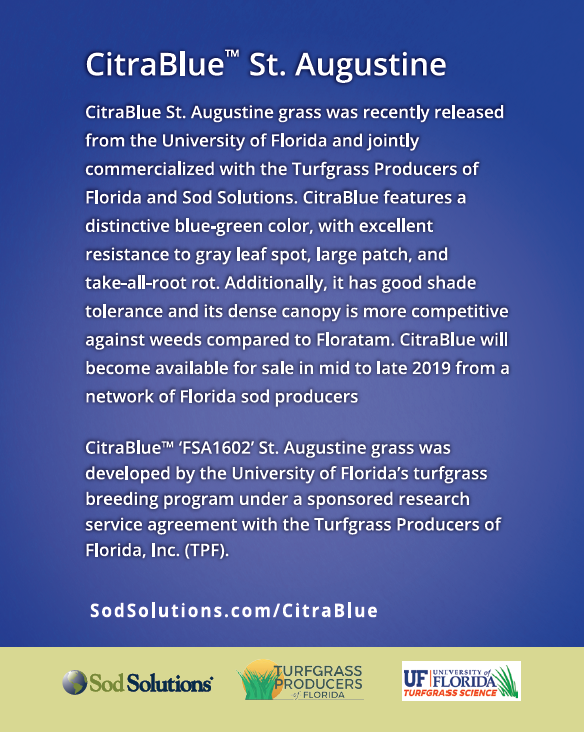

CitraBlueTM St. Augustinegrass (FSA1602) was recently released from the University of Florida and jointly commercialized with the Turf Producers of Florida and Sod Solutions. As of 2020, CitraBlue is now commercially available throughout Florida. While it can take months or even years for a turfgrass to become available to the landscape industry following its release, it takes even longer for a new turfgrass to be developed. Dr. Kenworthy offers some insight into the turfgrass breeding process and his newest turfgrass variety, CitraBlue St. Augustine.

What to Consider Before Starting a Plant-Breeding Program

Several aspects must be considered before initiating a plant-breeding program. These include identifying a species that needs to be improved (think of grasses like St. Augustine, zoysia or bermuda), targeting a trait or traits to improve (think of characteristics such as greater shade tolerance, increased density or improved disease resistance) and selecting a grass that will perform in a certain location or locations (think of the sub-tropical climate of South Florida).

Selecting a Species of Turfgrass

A selected species is, in some ways, determined by the location of the breeding program and breeding of grasses that are regionally adapted. Turfgrass breeding programs tend to focus on improving cool or warm season species, but typically not both within the same program. The turfgrass breeding program at the University of Florida, for example, focuses on warm season grasses.

Pictured above: CitraBlue St. Augustine in a residential application.

Next, it is important to understand the reproductive biology of the selected species. For instance, some species may only self-fertilize while others may only cross-fertilize. Furthermore, some species are both self and cross-fertile, while other species reproduce through a modified reproductive pathway known as apomixes. Apomixes is a type of asexual reproduction in which the female parent produces seed in the absence of fertilization by a male parent. The seed produced from apomixes are genetically identical to the female parent. Additional factors include whether the species is sold and planted as seed or sod. These factors will determine the breeding methods used for improvement.

Trait Improvements in a New Turfgrass Variety

Trait improvement can be affected by several factors:

-

- How variable a species is for a given trait (more variation allows for more improvement),

- How easy or difficult it is to screen and make selections, and

- Whether the trait is highly influenced by the environment or strongly controlled by genetic components.

A trait that exhibits good variation, is easy to screen and remains under the control of genetic components can be improved at a faster rate compared to a trait with limited variation, that is difficult to screen or is easily influenced by differing environmental influences such as rainfall patterns or soil type.

The Intended Use of a New Turfgrass Variety

The intended use of the grass will impact the level of information and years of evaluation required before commercialization. For example, a grass used on a golf course putting green may require more years of evaluation before it is widely accepted compared to a grass that is intended for use alongside roads or in landscape settings.

Pictured above: the color difference between CitraBlue and Floratam St. Augustine.

The Breeding Process of a New Turfgrass Variety

To understand more about the breeding process, consider St. Augustinegrass, which is a warm season turfgrass used throughout the Gulf Coast states and the Carolina coast. It is exclusively sold as sod and predominantly used in residential and commercial landscapes. A new cultivar must be well adapted to sub-tropical climates (i.e. south Florida) or have good cold tolerance for use in North Carolina and northern Texas.

Sod production advantages would include a good rate of growth, sod strength and quick rooting. A major objective would also include improved drought responses with a secondary objective being chinch bug resistance. A breeding program such as this would be initiated by collecting different St. Augustinegrass lines with known desirable traits such as:

- drought tolerance,

- shade tolerance,

- chinch bug resistance,

- disease resistance, and

- good production characteristics.

Controlled hand pollinations of all combinations would be made between the lines with a goal of producing 1,000 to 2,000 plants. These progeny plants would be planted in a large field where they compete for space while receiving only limited irrigation and fertilizer with no control of insects or diseases. After three to five years, selections would be made to narrow the group to 80 or 150 lines.

These selections would then be propagated and planted in a new replicated study where they would receive better management practices, such as mowing and fertilization, but again no control of pests. The plots would be routinely rated for turfgrass performance parameters. During periods without rain, the plots would be assessed for their ability to maintain quality during a drought. After three to five years, the number of lines would be narrowed to 15 to 30. The plots would again be propagated for new replicated experiments in multiple locations.

Again, they would be evaluated based on adaptation to multiple environments and would be closely monitored for quality during periods of drought. Controlled laboratory studies would then be performed to assess rooting traits and water use for drought responses and chinch bug activity. Survivability of chinch bugs would be assessed, and plots would be planted under shade.

During this time, small increases would be made to begin working with sod producers to gain their feedback on production characteristics. This stage of evaluations takes a minimum of five years. In total, this process takes 10–15 (sometimes more) years to identify the best line suitable for release. Following release, it typically takes two to three additional years for a grass to get increased and become commercially available.

The Expense of a Breeding Program

A 10–15 year turfgrass breeding program costs hundreds of thousands of dollars and requires the detailed attention of a dedicated team of researchers. CitraBlue St. Augustinegrass was developed by the University of Florida’s turfgrass breeding program under a sponsored Research Service Agreement with the Turfgrass Producers of Florida, Inc. (TPF).

The following TPF member farms supported the development of CitraBlue St. Augustinegrass through research contributions:

- A Duda & Sons

- Action Sod & Landscape Gardens

- Babcock Nursery

- Bay Breeze Farms

- Bayside Sod

- Bethel Farms

- Classic Turf

- Council Growers

- Florida Premier Turf

- H&H Sod Company

- JW Turf Farms

- K&S Sod Company

- King Ranch

- Lake Jem Farms

- McCall Sod Farm

- R.B. Farms

- S&K Sod Company

- SMR Farms

- Star Farms

- Tater Farms

- Travis Resmondo Sod

- TurfPro Services

- Woerner Agri-Business

- Woerner Farms

CitraBlue St. Augustinegrass

Pictured above from left to right: Floratam and CitraBlue St. Augustine.

CitraBlue St. Augustinegrass (photo right) features a distinctive blue-green color with excellent resistance to gray leaf spot, large patch and take-all-root rot. Additionally, it has good shade tolerance and its dense canopy is more competitive against weeds compared to Floratam (photo left).