The Lifecycle of a Turfgrass: From Development to Market

Why are there so many new turfgrass releases?

This question was recently answered at the Florida Turfgrass Association conference in November 2023. Mark Kann, the Director of Florida Operations for Sod Solutions, delivered a presentation addressing the recent release of several turfgrass varieties by turfgrass breeding programs from various universities. The presentation focused on how turfgrasses are developed and was accompanied by comments from Christian Broucqsault, the COO of Sod Solutions, and Ken Morrow, Founder of The Turfgrass Group. (Kann, Broucqsault and Morrow are pictured together following the presentation in the image above.) Attendees gained a deeper understanding of the complexities involved in turfgrass breeding and the commercialization of new varieties. Specific timeline examples were presented for the development of CitraZoy® Zoysiagrass, Celebration Hybrid® Bermudagrass, Cobalt® Hybrid St Augustine, TifTuf® Bermudagrass and Stadium™ Zoysiagrass.

Below is a synopsis of the presentation.

The Life Cycle of a Turfgrass: From Development to Market

The turfgrass industry is at an unprecedented time in the development and release of turfgrass into the market. The number of turfgrasses released and brought to market over the past decade is substantial. While some welcome this influx of varieties that provide various options for the end-user, others view it as crowding an already crowded market. However, it is important for sod producers to understand the lengthy process required to develop an improved turfgrass variety as well as for all turfgrass professionals to remain dedicated to supporting turfgrass research programs, whose aim is to deliver innovative products that will benefit the entire turfgrass industry.

The establishment of the Specialty Research Crop Initiative (SCRI) in 2010, has been a major driving force of so many turfgrasses being released. The SCRI was created to focus on drought responses to address water quantity and quality issues resulting from more frequent periods of drought and population growth. The SCRI originally consisted of University of Florida (UF), University of Georgia (UGA), Oklahoma State University (OSU), North Carolina State University (NCST) and Texas A&M University (TAM). This initiative has led to more cooperative research by sharing common cultivars and evaluating them at various locations to produce expedited data.

This article will discuss the various stages of the lifecycle of a turfgrass:

- Call for Research

- Funding

- Research and Development

- Product Release

- Establishment and Expansion

- Marketing and Education

Stage One: Call for Research

The lifecycle of a turfgrass begins with a call for research to meet the needs and demands of the industry. With turfgrass, we often seek environmentally friendly grasses requiring fewer inputs such as water/irrigation, fertilizer and pesticides. Improved tolerances such as drought, shade, heat/cold and pests (disease/insects) are often at the forefront of industry desires. Agronomic features such as growth habits, type of propagation (seeded vs. vegetative) and overall grow-in and maintenance requirements are critical for turfgrass producers and end-users. Finally, improved aesthetics is another crucial area of focus.

Calls for proposals can start at the university level by applying for grants (Federal/State). Some examples of these grants include the National Turfgrass Evaluation Program (NTEP) or the Specialty Crop Research Initiative (SCRI). These grants often help fund graduate students and support their research projects for several years.

Other calls begin with the industry which may work with land-grant universities to provide the means to develop a turfgrass for specific traits. Often, these lead to Invitations to Negotiate (ITNs). ITNs initiated by industry are usually referred to as early ITNs. These programs are typically funded by industry, but the work is done at the university level in cooperation with the funding research group. Those groups initiating the ITNs can be turfgrass associations such as turfgrass producers or other national, state or local associations in the turfgrass industry such as the Turf Producers of Florida (TPF), St Augustine Research Group (SARG), Turf Research North Carolina (TRNC), Turf Research Florida (TRF) and Turf Research Florida Zoysia.

Several of these early ITN programs have yielded successful turfgrasses with the assistance of the SCRI program, which are listed below.

- Brazos™ Zoysiagrass: Developed at the University of Florida with traits for enhanced drought, cold, and shade tolerance; funded by Turfgrass Producers of Florida – TRFZ.

- CitraBlue® St. Augustinegrass: Another University of Florida variety, noted for its disease and shade tolerance, funded by Turfgrass Producers of Florida.

- CitraZoy® Zoysiagrass: Also from the University of Florida, funded by TRFZ, with improved disease resistance and a finer texture.

- Cobalt™ Hybrid St. Augustinegrass: A Texas A&M innovation with improved tolerance to drought and cold, funded by St. Augustine Research Group (SARG).

- Lobo™ Zoysiagrass: North Carolina State University’s contribution, requiring lower maintenance with fine texture and resilience to drought and cold; supported by Turf Research North Carolina(TRNC).

- Sola™ St. Augustinegrass: From North Carolina State University as well, this cultivar stands out for Raleigh improvement and better cold and disease tolerance, with TRNC as the funding agency.

Other ITNs may be initiated by private companies such as Sod Solutions, the Turfgrass Group, the Scott’s Company, DIG Plant Company and Mountain View to name a few. Sometimes, turfgrass can be developed after discovery by an individual or producer. Examples of these turfgrasses are Palmetto® St. Augustinegrass and Classic St. Augustine.

Late-ITNs are typically initiated by the university through grant-funded research that produces turfgrasses that will benefit the industry. These ITNs are more of a bidding process, and most universities seek the most beneficial path to market and develop a turfgrass. Companies will often provide a plan to the universities, which will negotiate the terms of the agreement before awarding the rights to the proposed turfgrass.

Stage Two: Funding

Funding for research is accomplished at many levels. With early ITNs, the funding is collected by the industry group that initiated the ITN. The funding may come from a group of producers interested in developing a turfgrass with particular traits. Payments are often required annually for several years during the period of research

Some of the programs started by industry-driven early ITNs may be established as closed programs. Only those contributing to the funding will be eligible to license any varieties developed or released through the research process. This is done to reward the contributors that believed in the study’s objectives and funded the program.

Other programs may be established as joint release programs to help support the turfgrass producers in a particular area in exchange for their support in producing specific grasses. These types of programs have been established in Florida in cooperation with the Turfgrass Producers of Florida, in Texas with the Turfgrass Producers of Texas and in North Carolina with the North Carolina Sod Producers Association. These programs share the royalties between the turfgrass licensing company and the turfgrass producers’ associations in the respective states for particular grasses. There are often established criteria for joint-release programs regarding acres in production and the number of growers required to maintain the program.

The budgeting process for turfgrass begins very early in its development. Beyond the funding for research and development, budgets include funds for support of future marketing and education. Promoting a new grass requires fiscal resources, and the turfgrass proprietor must deliver these resources before collecting royalties. Once the expansion of a turfgrass gains momentum and is more recognized by end-users, royalties will come in to help fund future promotions. A great example of this type of marketing fund involves EMPIRE® Zoysiagrass in both Florida and the Carolinas. The Florida EMPIRE Marketing Group (FEMG) and the Carolina EMPIRE Marketing Group (CEMG) were established to promote EMPIRE, which provides funding for all marketing at trade shows, field days, media, etc.

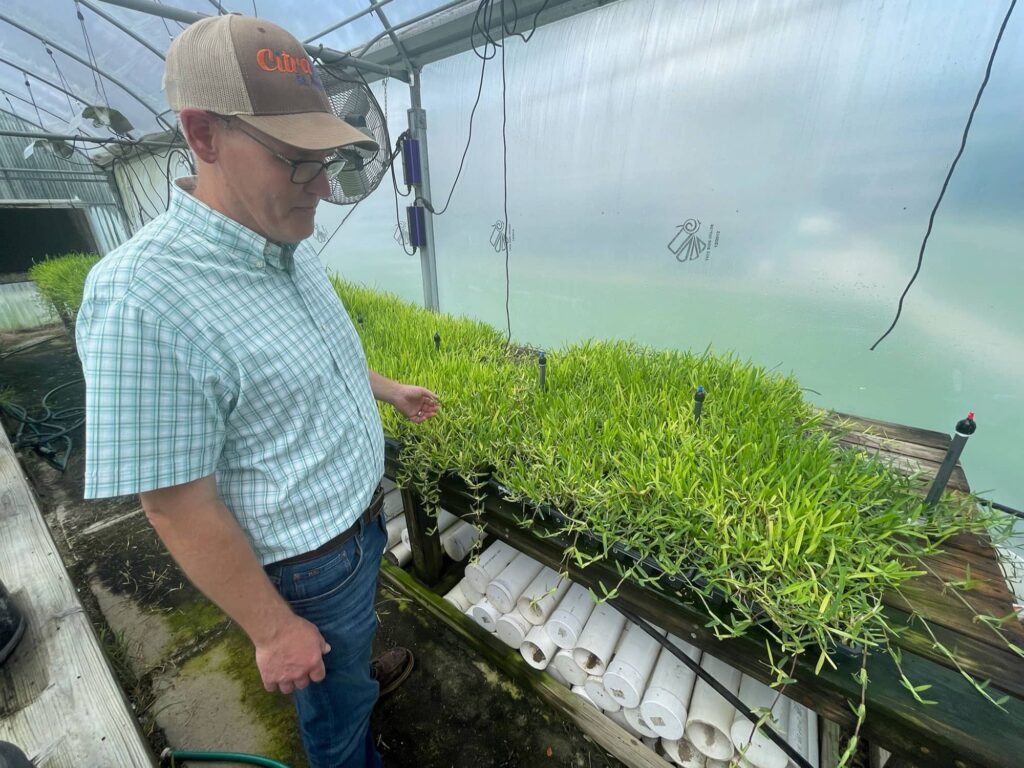

Plug trays grass varieties for research in a greenhouse.

Stage Three: Research and Development

The timeline for research and development varies among turfgrasses, with some being developed and released in 5-10 years and others taking more than 20 years. The longer a turfgrass can be evaluated, the more data can be provided. Still, once a turfgrass is released and agreements are made with universities to create license agreements, the clock starts ticking regarding payments back to the university that released the turfgrass. The timeline to begin paying minimum royalties, regardless of sales, is typically within the first 2-4 years after release. This puts more pressure on the licensor to move forward with further development and marketing of the turfgrass.

Several programs exist to help compare various cultivars at diverse locations to help researchers, evaluators and end-users gauge the potential of a turfgrass in a particular region or under specific conditions. The National Turfgrass Evaluation Program (NTEP) is one such program administered by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) based in Beltsville, MD. The program awards grants to university turfgrass researchers to establish and evaluate individual trials for 5-years. Trial locations are chosen to represent diverse regions and growing conditions where the species is well adapted and at a few locations that represent environmental extremes. Most trials are established for evaluation utilizing good management practices; however, a few trial locations will focus on specific stress factors such as shade, drought, winter kill and traffic. Turfgrasses are submitted by universities, private companies and others to be evaluated through the NTEP Program for a fee. In many cases, the turfgrasses are entered into the program for continued evaluation after university testing to compare to established commercial varieties and other new cultivars destined for release.

The Specialty Crop Research Initiative is another USDA pathway for evaluating turfgrasses at various locations. Since 2010, multiple researchers and extension faculty at several land-grant universities with turfgrass breeding programs have been sharing and evaluating experimental breeding lines of bermudagrass, zoysiagrass, seashore paspalum and St. Augustinegrass. This collaboration between university programs has expedited the identification of grasses with superior performance under variable environmental conditions. Since initially evaluating for drought/salinity tolerance, the SCRI has expanded its focus on other areas, including shade, wear and sod strength.

Field testing is essential to research and development, exposing new turfgrasses to real-world conditions. This is also an opportunity for evaluation by those who will be producing the turfgrass and end-users who will ultimately be installing and maintaining the grass on a golf course, sports field or landscape. Testing sites are usually selected according to the amount of cooperation and interest from a producer or end-user and geographical locations with varying climates and conditions. Evaluating grasses grown under various soil types, irrigation rates and maintenance practices is vital to developing a turfgrass.

Maintaining intellectual property typically involves signing a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA) with the producer or professional who wishes to evaluate the grass. MTAs usually establish guidelines that limit the reproduction of the original material to a specific size or acreage but typically allow for a producer to assess the expansion of the turfgrass. Once an MTA has reached the end of the agreement, depending on the status of the turfgrass release and/or certification status of the turfgrass, a producer may choose to license the grass or terminate the evaluation and destroy any remaining material.

Stage Four: Product Release

Many universities have Cultivar-Release Committees comprising faculty researchers in a particular area of expertise who evaluate the research conducted by the breeder. This peer-reviewed release mechanism assesses the proposed release and either approves the release for commercialization or recommends further testing.

With late ITNs, the university typically develops turfgrass with limited support from the industry or through grant-funded research. Once a grass is developed and a Cultivar-Release Committee decides to commercialize it, ITNs are sent to competing organizations, who then engage in a bidding process where each organization submits a proposal with their business plan and argues why they should be awarded the rights to a particular turfgrass. Financial terms may be set forward before the bidding process but are often negotiated after the awarding of the grass. These terms include the percentage of royalties paid to the university and other fees. Once an agreement is established and agreed upon, a master license is constructed, which results in the distribution of sublicenses under the owner of the master license.

The protection of intellectual property once again comes into play as the turfgrass is patented, and once a name is established, the name will be protected under a trademark. Once a name is trademarked, only licensed producers may legally sell that particular turfgrass under its trademarked name. Additionally, the turfgrass must be registered with the respective state AOSCA (Association of Seed Certifying Agencies) entity, and the responsible turfgrass proprietor must provide AOSCA with a description and any supporting data for that turfgrass cultivar.

The protection of intellectual property once again comes into play as the turfgrass is patented, and once a name is established, the name will be protected under a trademark. Once a name is trademarked, only licensed producers may legally sell that particular turfgrass under its trademarked name. Additionally, the turfgrass must be registered with the respective state AOSCA (Association of Seed Certifying Agencies) entity, and the responsible turfgrass proprietor must provide AOSCA with a description and any supporting data for that turfgrass cultivar.

The amount and timing of royalty payments varies by turfgrass and university. Many of these royalties may be time-based, meaning that a minimum royalty must be paid to the university regardless of current turfgrass sales, while others may be solely based on the sale of turfgrass. Producers (sub-licensees) often pay royalties to the master licensor, who will return the pre-determined portion of royalties to the university that released the turfgrass. Usually, royalty payments from producers are based on the amount of square feet sold, typically every month. Other royalties may be based on revenue and/or the production acres.

Stage Five: Establishment and Expansion

Much care should be taken to establish proper procedures for establishing and expanding a turfgrass to ensure genetic purity. Establishing clean, pure-genetic material is essential in any successful turfgrass program. Often, breeders cultivate plug trays to establish a “Breeders Block” of material distributed to licensees to develop a seed block for future expansion. The material can be distributed as sod or sprigs depending on the availability and ability to harvest as such. These seed blocks are often as small as a few thousand square feet up to 10-20 acres in size, typically depending on the variety and availability of material.

There are standard classes for all AOSCA agencies that follow particular guidelines for the certification of turfgrasses. Each time a grass is expanded or planted from existing material, it will drop one class according to the AOSCA guidelines. The classes are in descending order: Breeder, Foundation, Registered and Certified. Most AOSCA agencies will assist with inspecting the Breeder Class; however, it is the ultimate responsibility of that particular breeder to ensure that the field area remains genetically pure. Some breeders may restrict access to this Breeder block to a specific period or a certain number of harvests before removing the breeder stock label. Depending on the state agency and the breeder, the field may be reclassified as foundation or registered. If the breeder feels that the field has become compromised, they will ask for it to be killed and removed.

The certification of turfgrasses is mainly used for turfgrasses used on higher-end locations, including golf courses and sports fields. Most turfgrass professionals want the reassurance that they purchase genetically pure material from a licensed grower. Turfgrasses that are to be in the certification program require that the sod producer submit an application indicating the location, size of the area, turfgrass cultivar, where the seed stock for the area came from and proof of fumigation. Most certified grasses are bermudagrasses in the southern states, along with some zoysiagrasses and seashore paspalums.

In some cases, accreditation programs have been established for grasses that do not usually fall under the certification program, such as home lawn grasses, including St. Augustinegrass and zoysiagrass. These programs help to control the expansion of turfgrasses and ensure that they are being derived from genetically pure material. Sod Solutions established the Sod Solutions Accredited Licensed Turfgrass (SALT) Program in cooperation with several universities as a way to help ensure that proper methods are being followed in the expansion of newer turfgrasses. Some newer turfgrasses eligible under this program include CitraBlue, CitraZoy, Lobo, Cobalt and Sola.

In some cases, accreditation programs have been established for grasses that do not usually fall under the certification program, such as home lawn grasses, including St. Augustinegrass and zoysiagrass. These programs help to control the expansion of turfgrasses and ensure that they are being derived from genetically pure material. Sod Solutions established the Sod Solutions Accredited Licensed Turfgrass (SALT) Program in cooperation with several universities as a way to help ensure that proper methods are being followed in the expansion of newer turfgrasses. Some newer turfgrasses eligible under this program include CitraBlue, CitraZoy, Lobo, Cobalt and Sola.

Stage Six: Marketing and Education

The most prolonged or never-ending stage of the turfgrass lifecycle is marketing and education. Along with development, education should be an ongoing activity. It is the key to continued improvement and feedback from every level, including producers, industry professionals and end-users. At times, it may seem overdone or unnecessary. Still, every attempt should be made to get as much information as possible to the largest number of customers utilizing various methods of communication.

Marketing and education occur at various levels and to different degrees for different groups. With turfgrass producers, often this is the easiest and most cost-efficient group to reach due to frequent visits to their farms and interactions at association meetings, research events and field days. This type of relational marketing is easily and opens other avenues to reach other potential customers affiliated with the producers.

Lobo™ Zoysiagrass on display at the 2022 NCSU Lake Wheeler Field Day.

In terms of marketing and educating trades and industry personnel, it becomes more challenging to reach your intended audience. Much of this type of marketing is done by advertising in trade publications and journals to engage golf course superintendents, sports field managers, specifiers or landscape managers. Also, promoting turfgrasses at various trade shows and conferences is a great way to interact with potential customers, but you are often limited to those in attendance.

Finally, end-users are the most challenging and cost-prohibited group to reach and educate. The sheer numbers of potential customers at this level make it expensive to make an impression and even more difficult to educate appropriately. The most common options for reaching this level of customers are television and radio advertisements, billboards, digital banners, social media ads and various publications.

Regardless of your intended customer base, continuous marketing and education will continue to provide a lifeline to help create turfgrass brands that can stand the test of time and be recognized for decades.

In summary, the lifecycle of a turfgrass can vary significantly between different cultivars. The stages can also often overlap and occur in different orders.

This article was written by Mark Kann, director of Florida operations for Sod Solutions.